Part 1: (Published in comics cover-dated) August 1984

The rise of the Comics Code Authority

(Over the past half-dozen months, Charlie’s shepherded us from the 1960s to the 1980s, following the development of the independent comics market. In this, the first of a new series tracing the history of comic book regulation, Charlie sets the Wayback Machine for the year 1954, when psychiatrist Fredric Wertham wrote: “What is the social meaning of these supermen, superwomen, superlovers … super-ducks, super-mice, super-magicians, super-safecrackers? How did Nietzsche get into the nursery?”)

DURING THE FIRST half of the 1950s, the comics industry was selling about a billion magazines a year. At 10¢ a copy, annual sales were totaling about 100 million dollars.

So it was probably inevitable that someone—it turned out to be Dr. Wertham—would ask what effect all those comics were having on kids.

Based upon his seven-year study, Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent presented a damning picture of the industry—although it was a picture painted with questionable logic and shaky research methods.

NEVER MIND ALL the other changes the United States faced at the same time—the automobile-assisted flight from city to suburbs, urban blight, the Cold War, a recession, race tension.

As Don Thompson, now editor of the Comics Buyer’s Guide, wrote in a collection of essays entitled The Comic-Book Book, “Instead of setting up control groups of children who read comics and children who did not … Wertham found juvenile delinquents and asked them if they read comic books. Since nearly every kid read comics in those days … the answer was almost always affirmative. … Juvenile delinquents read comic books, therefore comic books cause juvenile delinquency. What could be plainer?”

Whether Wertham’s book was fair or reasonable, it struck a nerve. The American Legion, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, the National Organization for Decent Literature and others began passing resolutions, conducting boycotts and publishing monthly evaluations of comics.

LATE IN 1954, San Francisco-area Safeway food stores announced they were dropping all comics. Denver Safeway stores followed suit. Some parents publicly burned comics.

Several comics publishers got the message. They decided to try a plan for self-regulation—so the government wouldn’t do it.

The first plan—The Association of Comics Magazine Publishers (ACMP), formed in 1948—flopped because the big companies refused to participate. These included National (now DC), Dell (the Disney titles, among others), and Fawcett (Captain Marvel).

These publishers said they didn’t want their image used as a cover for publishers of inferior products.

|

| Click to see full-size |

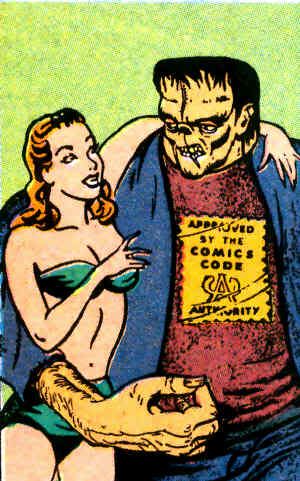

It incorporated just about all the old ACMP rules: no favorable treatment of criminals; no unfavorable treatment of police; no sadism, torture, “sexy, wanton comics,” vulgarity, obscenity, excessive slang, religious or racial slurs.

The Code added some new bans: no vampires; no ghouls, no ads for tobacco, liquor, knives, guns, gambling equipment or salacious items; no use of the words horror or terror in a magazine title; no use of the word crime alone on a cover.

THIS TIME, IT worked. With an anxious eye toward those hordes of boycotting, burning moms and dads, 24 of the nation’s 27 comics publishers agreed to submit their books to the Comics Code for approval before publication. Dell still refused, but it ran its own “Pledge to Parents” prominently in each issue. Dell’s successor printer-owned publishers, Gold key and Whitman, maintained the Code-free tradition.

As it turns out, the creation of the Comics Code came just in time to save the industry from the wrath of the Senate Subcommittee to investigate Juvenile Delinquency.

Stay tuned. Next: The Men Who Cracked The Code.

(Charlie Meyerson is the morning news anchor for WXRT Radio, Chicago.)

Part 2: September 1984

Cracking the Code

STIRRED UP BY Dr. Fredric Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent, state lawmakers across the country late in 1954 began to form “study groups” to examine the dangers comic books posed to the youth of America.

Some state legislatures and city councils passed laws banning the sale of “crime comics” to kids under 18. Generally, those laws didn’t survive challenges in the courts or vetoes from mayors and governors.

That was the atmosphere as the U.S. Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency began to study “the comic book menace.” One of the star witnesses was William M. Gaines, then publisher of EC Comics (now Mad Magazine)—well known by fans for its wonderful art and creative scripting, but then under fire for graphically depicting adultery, ax-murders, kids killing their parents …

“JUST FOR THE RECORD,” Gaines told me in 1978, “I requested the right to appear. Having requested it, I was subpoenaed. But I requested it, and I don’t want it to sound like I was dragged there.”

Gaines was in fine form to begin the hearing. His opening statement defended American kids as “citizens, entitled to select what to read. Do we think our children are so evil, simpleminded, that all it takes is a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery?”

Gaines was taking an appetite suppressant; at a key point in the hearing, it began to wear off, dulling his senses. The result was a public-relations disaster. He wound up attempting to defend an almost indefensible cover—a man with a bloody ax holding the severed head of a woman.

Gaines was taking an appetite suppressant; at a key point in the hearing, it began to wear off, dulling his senses. The result was a public-relations disaster. He wound up attempting to defend an almost indefensible cover—a man with a bloody ax holding the severed head of a woman.“A COVER IN bad taste,” he said, might have “the head a little higher so that the blood could be seen dripping from it.” Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee noted there was plenty of blood on the cover as it was.

The days to follow brought a fresh wave of public criticism of Gaines, EC Comics … and of the industry.

Still, the subcommittee wound up its work rejecting “all suggestions of governmental censorship as being totally out of keeping with our basic American concepts of a free press operating in a free land for free people.”

In Kefauver’s words, “the public must be sold this idea of restricting purchases of comics to those carrying the (Comics Code) seal of approval.”

|

| Click to see full-size |

Among its first victims were EC Comics: no room for EC’s best-selling Vault of Horror and Crypt of Terror under a code that banned the words “horror” and “terror” on comic book covers!

“I dropped the books I dropped,” Gaines says, “not as a result of the committee’s investigation, but as a result of wholesaler pressure, which was brought about by dealer pressure and parent-teacher-group pressure.

“The horror books made money right up to the last issue. The other books had been losing money anyway.”

A FEW POST-CODE EC titles with thrilling names like Psychoanalysis didn’t last more than a few issues. Their deaths demonstrated the real muscle behind the Code: magazine distributors.

As Frank Jacobs writes in his biography of Gaines, “Stack after stack came back, unopened by wholesalers … (because) they didn’t bear the (Code) Seal of Approval.”

For most of the next two decades, the Code was as good as law. Between 1954 and 1969, according to comics historians Reinhold Reitberger and Wolfgang Fuchs, the Comics Code reviewed and approved 18,125 comics titles—the vast majority of U.S. comics sold during the time.

THE PEOPLE WHO created the Code were concerned comics might encourage violence among kids. Under the Code, though, kids may have found violence more attractive. Code rules prompted scripters to make gunplay look like a game: no one suffered; the good guys never killed anyone.

In the words of Reitberger and Fuchs, they just “planted the bullets with breathtaking precision into a man’s upper arm, or shot their opponents’ guns clean out of their hands.”

IN 1971, Stan Lee decided to do a three-issue Spider-Man story about the dangers of drug addiction. Then-Code administrator Leonard Darvin said no.

IN A DECISION that made the pages of The New York Times, Lee published the issues anyway—without the seal.

The issues sold as usual. Distributors, retailers and readers didn’t seem to notice.

But the Comics Code Authority noticed. On April 15, 1971, Code officials unanimously adopted the first changes in the Code, allowing “narcotics addition … presented (only) as a vicious habit.”

WHILE THEY WERE at it, they modified the Code to allow vampires, ghouls and werewolves to appear again in the pages of comics; to allow comic book police to die in the line of duty and comic book public officials to break laws, as long as the guilty were punished.

A few months after the changes, DC Comics published a Green Lantern/ Green Arrow story similar to the SpiderMan story that prompted the changes. It won Code approval.

But the Code had cracked. It clearly wasn’t the power in comics it had been. More on that story next time.

(If you are interested in reading more about Bill Gaines and the development of the Comics Code, look up a copy of Frank Jacobs’ The Mad World of William M. Gaines (Bantam Books, 1973) and a long interview with Gaines in The Comics Journal #81, May 1983. And you might be surprised how much comics history you can unearth at your friendly neighborhood public library.)

(Charlie Meyerson, as ever, remains employed as a reporter and morning news anchor at WXRT Radio, Chicago.)

Part 3: November 1984

Why bother with the Comics Code?

THE COMICS CODE Authority? That little seal in the upper right-hand or lefthand corner of most newsstand comics?

Eric Olson said he’d never heard of it. You might find that surprising, considering he’s the magazine buyer in charge of comics for the Chas. Levy Circulation Company, maybe the biggest magazine-distribution concern in the nation.

Levy delivers about three million comic books a year to Chicago-area retailers. But as far as Olson knows, no one in the country pays attention to that little seal.

That’s not surprising to the man who administered the Comics Code for more than 20 years, Leonard Darvin, who describes himself as an old retired guy” still serving as lawyer for the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA), which created the Code.

“CHARLES LEVY,” Darvin says, “certainly was one of the wholesalers that had a great deal of trouble with the opposition to comics published in some measure—most comics were OK even then—in 1952 and 1953.

“Of course, times have changed. They had a change in personnel; they’ve had no difficulty with comics. They assume the Code is sort of built-in, without even thinking about it.”

Times have changed, indeed: thirty publishers originally held membership in the CMAA, now there are three—Marvel, DC and Archie—along with their three national distributors, and World Color Press and Chemical Color Plate.

In the summer of 1979, the CMAA turned over its management to a timesharing firm, Trade Group Associates, which also handles work for organizations representing hardware manufacturers and women in publishing.

Dudley Waldner, who followed Darvin as Code Administrator, oversees two reviewers charged with checking every page of books published under the Code.

ONCE, THE CODE AUTHORITY kept watch for anything less wholesome than Nancy Drew mysteries; now, because the Code and the times have changed, the Authority allows material considerably more risqué:

- Despite a Code requirement that women be “drawn realistically, without undue emphasis on any physical quality,” you don’t have to look through too many Code-approved comics to find at least a couple of qualities unduly emphasized.

- Despite a ban on portrayal of “illicit sex relations,” stories involving extramarital sex appeared under the Code last year.

- Despite the prohibition of “gruesome illustrations,” another Code-approved book showed a boy about to explode in the vacuum of space.

|

| Click to see full-size |

“You don’t have to go very far to be able to see things much stronger than the strongest comic books and far more negative than the most negative comic books.”

Under the direct-sales system, publishers now can reach a growing audience without having to satisfy distributors and retailers who once insisted the Code approve all books. Marvel and DC are expanding their direct-sales lines—which do not go through the Code Authority.

Direct-sales versions of Marvel’s regular newsstand comics do not carry the Code seal, even though they have earned it.

IF DISTRIBUTORS AREN’T watching to see whether books pass the Comics Code: if the Code Authority itself is a “shell of its former self,” in Giordano’s words; if publishers have an efficient means to sidestep the Code, then why bother with it?

“That’s a good question,” Giordano says. “We haven’t answered that yet, internally. I guess maybe ‘old habits die hard’ is the best reason I can think of.

“We recognize that the Code as it now functions probably doesn’t serve any real, worthwhile advantage—with the possible exception of having us be able to say to parents that we pass material through the Code without really telling them what that means.” Code Administrator Waldner points out that the CMAA aggressively publicizes the Code, distributing free copies to parents, teachers and librarians.

Darvin says the Code is important to the industry. Referring to the 1971 decision allowing comics to deal with the problem of narcotics, Darvin says the beauty of the Code is that if it is not doing the job, the industry can change it: “They themselves made the change, and they can make it again, if time comes along that it should be made.

“But just to throw it out the window and not have any restraint will cause difficulties.”

IN COMICS SHOPS across the country, Code-approved books are sold side-by-side with direct-sales comics without any external restraint.

Darvin recommends “these new fellows … use legitimate material (because) even though the market today—especially in these comic book stores—basically caters to the teenagers, they’re still basically children’s publications.

“It isn’t a question of being blue-nosed about it. It’s a question of what you’re selling. Just as prime-time television can not have sexual intercourse on the air—you try it on prime time and you’re going to knock off television—you try certain things in comic books and you’re going to knock off the comic book industry, whether it consists of the traditional publishers or the new ones.”

NEXT TIME: What publishers are doing to prevent the industry from being “knocked off.”

(Charlie, who reports weekday mornings on WXRT (93.1 FM) in Chicago, recommends you read Dr. Seuss’ latest work, The Butter Battle Book, before it’s too late.)

Part 4: December 1984

Can the Code be saved?

|

| Click to see full-size |

An article that could trigger those concerns appeared in the February 1984 issue of Psychology Today. Amherst professor Benjamin DeMott surveys a few of the new direct-sales comics (like the one you’re reading), which do not pass through the Comics Code Authority for approval.

He refers to them as “adult comics,” noting a new “frankness about sex.” He offers a “guess” that most readers of “adult” comics are “dropouts and community-college students”—“young losers” who take comfort in what he calls “the gloom, the pervasive atmosphere of defeat in comics,” from the oppression of American Flagg’s Plex to the double-crossing President in Camelot 3000.

Never mind that DeMott passes judgment without waiting for the story’s resolution; never mind that he doesn’t distinguish between direct-sales comics and regular, Code-approved newsstand titles. This is the stuff of which anti-comics crusaders are made.

DC COMICS EXECUTIVE Editor Dick Giordano says he doubts a new dark age is likely. He’s not required to send any comic book through the Comics Code. But he does have his own code:

“I’m not willing to accept anything in terms of violence, sexual innuendo, strong language … not absolutely required by the story line (or) with a view to titillation. I will permit any of those things if it’s absolutely necessary to the telling of the story.”

Mike Gold, First Comics’ editor and a former broadcaster, may be a little more liberal. Gold would accept anything that would pass on contemporary radio—if it makes the story work.

GIORDANO SAYS DC has been trying to persuade the Comics Magazine Association of America (CMAA) to do something to counteract the bad press comics can get. But he believes “a trade group that has just three of 16 publishers as its members probably can not serve any real function.”

Giordano would like to gather all publishers in a new organization “that might use the CMAA as its base … so we could solve common problems—marketing problems, publicity problems.”

So far, First Comics—among others—has refused to go along. Publisher Rick Obadiah says he supports the idea, but not as long as it is tied to the Comics Code, which he says has a history of censorship.

YOU WANT TO KNOW what I think?

The concept of Comics Code approval as a prerequisite for national distribution is dead. The direct-sales market now distributes comics nationwide, with or without a Code Seal.

The Code has survived primarily as a defense against criticism, so the industry can-in Giordano’s words—“be able to say we pass material through the Code.”

Publishers seem just to be going through the motions. Critics – like DeMott—and distributors aren’t paying attention to the Code. Whether or not it was a good idea to begin with, it is almost useless now.

YET THE CODE ITSELF is a good set of guidelines for people creating comics for children. It requires that bad guys be punished and wrongs be righted; it says guns and drugs are bad; it encourages use of good grammar.

Rather than scrap it—as some critics propose—the industry could revive the Code.

The pressure of the 1950s is off. Publishers don’t have to apply the Code to all newsstand comics. Doing that has devalued it. Publishers could apply it more selectively – to comics whose creators are willing to follow it.

Maybe the CMAA would administer a code, or maybe it would authorize its member-publishers to use the Code Seal as they see fit. But the Code need not represent censorship. Properly promoted, it could be a big help—like a “Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval” for publishers hoping to persuade parents to buy children’s comics for their kids.

A trade organization is just the kind of group to do that promoting.

IF COMICS ARE IN danger of some new Seduction of the Innocent-type crackdown, it is because the public still sees comics exclusively as — in Comics Code administrator-emeritus Len Darvin’s words—“children’s publications.”

The industry needs to establish that comics are a medium as versatile as any other, capable of communicating with kids or adults. A well-funded joint effort to get the idea across—in TV, radio and print ads—would make the prospect of complaints about adult comics falling into kids’ hands as remote as complaints about adult books falling into kids’ hands.

For decades, mainstream bookstores have displayed children’s paperbacks among more “adult” books. In almost any supermarket you will see “Peanuts” collections displayed just inches from sleaze. Why no complaints of dangerous “adult” books being sold to children?

Paperback book publishers use cover design to steer kids to the right titles—a lot of children’s books use cover borders, where adult books’ cover illustrations run off the edge. Book publishers also establish special divisions for children, such as Dell’s Laurel Leaf line.

If nothing else, all that helps guide retailers. Already changes along those lines seem to be taking shape in the comics field: Marvel and DC are talking about establishing children’s lines; Giordano has said he’s considering establishing a separate cover format for DC’s entries.

IN A LOT OF WAYS the comics industry is coming to resemble the rest of the book industry. For instance, as the “trade paperback” has become popular in the mainstream, comics of similar size and format have become popular as “graphic novels.”

And, as Comics Buyer’s Guide columnist Heidi MacDonald has noted, the word-balloon-and-picture format is invading the mainstream. One week The New York Times bestseller list included three Garfield books, Berke Breathed’s Loose Tails and Gary Larson’s Beyond the Far Side.

MacDonald argues—correctly, I think—that before the comics can reach maturity, they have to develop material to attract people with interests broader than capes-and-leotards. And she says they have to win respect as a medium.

On the first count, the industry’s making progress. As for the second, overhauling Comics Code enforcement and establishing a strong industry-wide trade group would help.

(Broadcast newsman Charlie lives in Oak Park, Illinois with his wife, Pam and his cat, Mimsy, neither of whom is particularly fond of comics.)

Notes on the resurrection of this series, whose creation predates my ownership of a computer and therefore was written using a, you know, typewriter: These pieces were digitized using Google Docs’ ability to extract text from any graphic image—in this case, from scans of the published comic book pages. The process is impressive, but not perfect. Holler if you find typos. If I ever find additional tapes of interviews conducted for this series, I’ll digitize and share them here.

Enjoy this? Check out the precursor: “Scapegoat in Four Colors,” a history of comics and censorship. And this blog contains lots more about comics and pop culture. Subscribe—free—by email to get the latest.

Previously posted to this page.

Part 1: Scapegoat in Four Colors.

Part 1: Scapegoat in Four Colors.Part 2: Cracking the Code.

Part 3. The Comics Code Authority.

Part 4. Overhauling the Code.

(First posted to this blog August 25, 2011. Updated with direct links, May 2016.)

No comments:

Post a Comment